Sei sul sito colloca1.interfree.it

CHURCH OF SAINT SOFIA

IN BENEVENTO

HISTORY

The church of St. Sophia was founded by the duke Gisulfo II and completed by Arechi II, king Desiderio’s son-in-law, when he became duke of Benevento.

It was built near a Benedictine monastery and finished in the year 760, perhaps as the national church of the Longobards, and it was the most daring and odd structure of the Middle Ages.

Arechi II added a nunnery, joining it to the pre-existent Coenoby, so that it became a unique monastery and, perhaps thanks to Paolo Diacono’s suggestion, he called it St. Sophia, that is Saint Wisdom, in similarity to the famous Justinian temple of Constantinople.

This monastery, thanks to donations and legacies, became one of the most powerful of Southern Italy; it was at the apogee of its fame in the 12th century and not only for its monumental church, but also for its "scriptorium" where the "writing of Benevento", famous in the world, was used.

The church was well-known abroad and a French troubadour of the 12th century told about a marriage of a king celebrated there.

But history remembers that St. Sophia saw the youth of Abbot Desiderio, then Pope Vittore III, the famous Paolo Diacono, Popes (for example Onofrio II and Alessandro III) and kings, as Emperor Lotario and the Norman king Ruggero II.

Then the monastery declined and the Benedictines abandoned it in 1595.

ARCHITECTURE

The church is very interesting in the field of the European architecture of the first Middle Ages.

It is small, its diameter measures 23.50 metres. The external walls are 95 centimetres thick and made of tuffs and little bricks of 3 centimetres. The general plan is very original and new for the age and it is not derived from Roman or Byzantine examples. The central core is a hexagon, with six great columns at its apices. Arches on which the dome develops link the columns. Near the hexagon there is a decagonal ring with eight pillars and two columns just after the entrance. The pillars are not ranged according to the classic canons, but in a radial way with the sides oriented differently and parallel to the external walls at the back. The perimeter is particular: first circular, then interrupted by walls in the shape of a star, and finally circular again near the main entrance.

All this creates games of perspectives, illusionistic and geometric effects, fruit of an original building understanding.

An example of this is the extraordinary vault variety, due to the unusual combination of the hexagonal crown and the decagonal one: the vaults are first quadrangular, then rhomboid and finally triangular, perhaps to remember the shape of the Longobard tents.

The splendours of the old church are also testified by the remains of the frescos in the apses, which reveal a wide-ranging work and a great expressive power, even if in their fragmentariness.

.

THE FRESCOS

The church was totally painted. The fragments are still visible in the apses, on a pillar, at the base of the cupola and in the edges of the shaped star walls.

Surviving elements of the cycle of Christ’s history are in the two side apses. The cycle of St, John the Baptist is in the left apse, where we can still see two scenes: the Announcement to Zachary and Zachary dumb.

The Virgin’s life is in the right apse and we can see the Annunciation and the Visitation.

THE RESTORATIONS

St. Sophia has changed its aspect during the centuries.

MEDIEVAL RESTORATION

In the 12th century the church was restored for the first time. The original plan remained intact. On the left side of the façade a campanile was added and at the entrance a little portico based on four columns. For these extensions the façade, originally nine metres long, was partially pulled down. Above the new portal, in the central lunette, a bas-relief was inserted. Today this bas-relief is on the church front door. In it we can see Christ in throne, on the right the Virgin, on the left St. Mercury martyr (he was a Roman soldier and his relics buried in 768, rest under the altar in the right chapel) and a kneeling monk, perhaps the Abbot John IV, the church restorer. Inside, the two entrance pillars were replaced with columns and in the central hexagon a "schola cantorum" was placed.

BAROQUE RESTORATION

In 1688 an earthquake razed the town. It also caused a very great damage to St. Sophia.

The central dome collapsed; the Romanesque campanile crashed down on the prothyrum, which was completely destroyed.

The baroque restoration in 1698, due to the Archbishop Orsini – later Pope Benedetto XIII – introduced great changes with the consequent loss of the ancient Longobard shape and the destruction of the precious frescos of the 9th century.

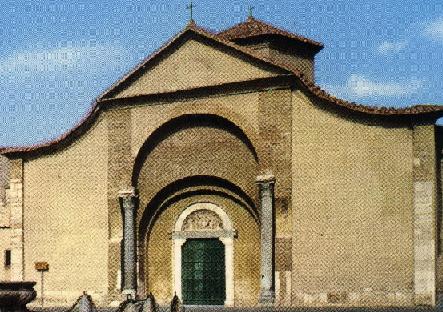

The star-shaped plan became circular, the central apse was demolished and rebuilt, the eight pillars were tapered and a new façade, still extant, was realized. Moreover, two lateral chapels and the sacristy were built. The inside was completely plastered and furnished according the Baroque style.

MODERN RESTORATION

In 1951, the Monuments Office of Naples began the restoration works, which brought again to light the original Longobard building plan. The two chapels, the central apse and the circular walls were demolished. The star-shapes walls were rebuilt thanks to the indications of the archaeological researches. The two great windows and the rose window on the Baroque façade were removed, while the portal was placed in the original position.

Aprile 2001 - Sito in allestimento

For information:

colloca1@interfree.it